Designing Outdoor Science and Environmental Education Distance Learning Experiences

By Emilie Lygren, Kevin Beals, and Jedda Foreman

What can effective virtual outdoor science experiences look like? Amid school closures and the suspension of in-person programming, this is a pressing question in the field of outdoor science and environmental education. Like many others, we are just starting to dip our toes into best practices in distance learning. While we know distance learning can’t replicate every aspect of an in-person experience, we can still use research on how people learn to guide our design of virtual offerings. The insights below are from our experiences and expertise in teaching and learning in general, doing distance learning with adults, watching lots of videos aimed at learners, and talking to many folks about their distance learning experiences with kids. This document is a work in progress as we, like many of you, get more and more familiar with emerging best practices in distance learning.

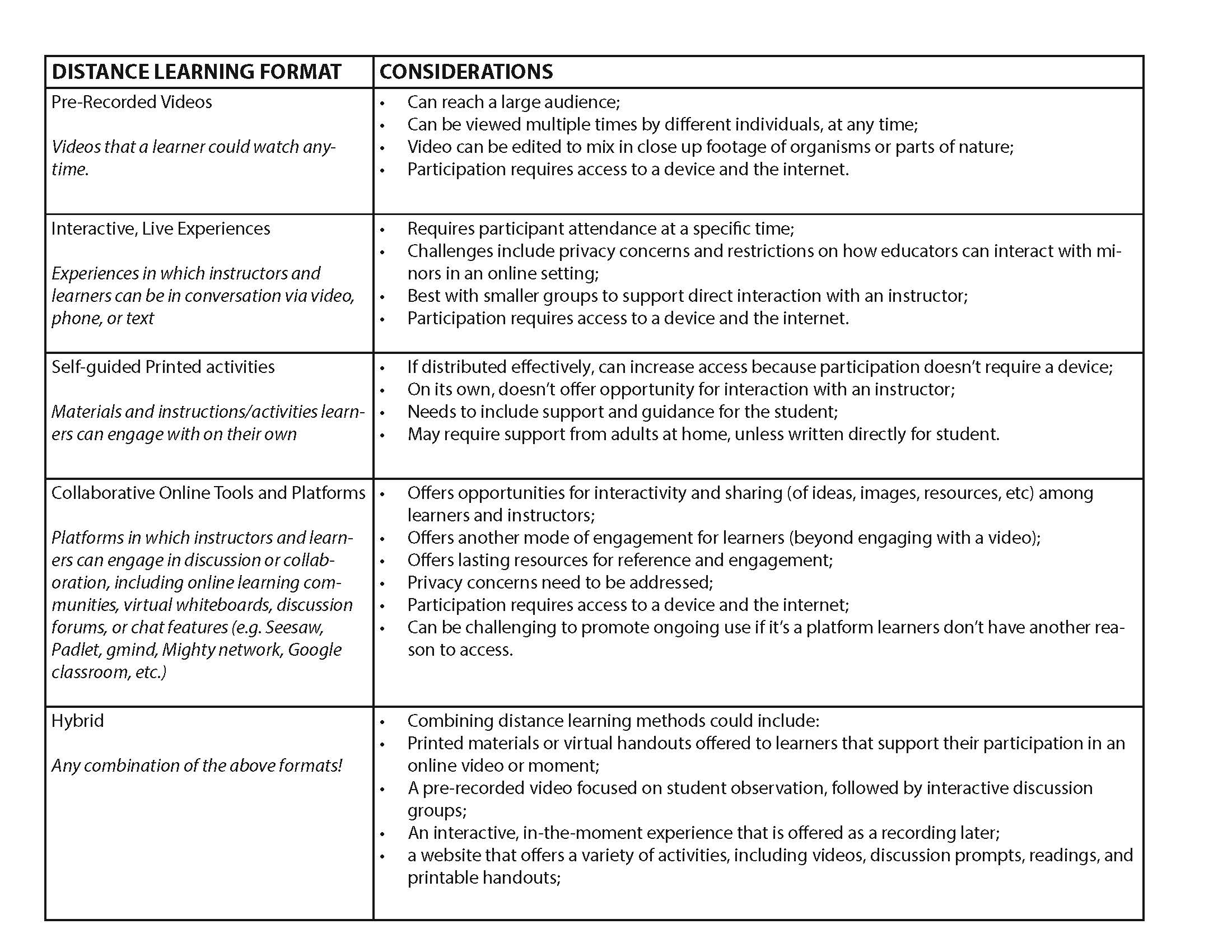

Note: When we say “distance learning”, we are referring to learning offered at a distance, including videos, online discussions, interactive virtual discussions, printed materials distributed, etc.

In this blog, we’ll:

- offer considerations for beginning design with clear goals and audience in mind;

- describe a few formats for distance learning,

- share some principles and reminders for designing effective learning experiences of any kind, including specific recommendations for distance learning settings.

Identifying a Goal and an Audience

What are the goals and intended audience(s) of your distance learning or online communication? Thinking about the purposes or goals and the intended audience(s) is an important first step. The format, content, tone, and focus of the distance learning experience may look different depending on your goals. Focusing on the intended audience(s) as you’re designing a virtual learning experience can guide you in making sure your offering will be accessible to those you hope to reach. Some possible purposes or goals for distance learning:

- Replacing content or experiences that would have taken place during in-person programming.

- Keeping the brand of your program alive and in the consciousness of schools, families, and learners.

- Offering a new kind of programming, virtually.

- Supporting classroom instruction.

- Creating resources that can be used post-pandemic as pre/post outdoor experiences.

- Gaining new followers or engaging new audiences and potential clients.

If you’re designing distance learning experiences and hope to primarily engage an audience of individuals who would have attended in-person programming, think about how to equitably and effectively engage that audience. What are existing pathways of communication, or established groups who are already communicating with families, with whom you might collaborate? If you are an organization that typically coordinates with classroom teachers or school districts to bring learners to your program, you’ll probably be able to reach your intended audience more effectively and more equitably by reaching out through schools and districts, rather than by reaching out to individual learners and families. Schools and districts have systems in place for distance learning. How can you build on what schools are already doing to support equitable access to distance learning? Some organizations are working with their county offices of education to engage learners through interactive “classroom visits,” pre-recorded video content, or live streams on social media pages. Working with schools, teachers, districts, or community organizations can benefit your audience by streamlining how they are receiving distance learning; promotes equity by building on distance learning methods and systems already being designed to meet the needs of a community, and can benefit you by offering a direct connection to the audience you hope to engage. Additionally, consider equity in terms of what learners will need in order to participate fully. Consider what a learner might need in order to access your learning experience, including guidance/support from an adult, and how you are going to ensure equity of access to those resources.

Applying BEETLES Design Principles to Distance Learning Experiences

Distance learning is an emerging and new horizon for the field of outdoor science and environmental education. In an Education Week article summarizing research on the effectiveness of online learning, Susanna Loeb writes: “Some students do as well in online courses as in in-person courses, but, on average, students do worse in the online setting, and this is particularly true for students with weaker academic backgrounds.” (Loeb, 2020). This research highlights the importance of making online learning experiences as effective as possible, and designing learning experiences that especially reflect the needs of learners who have been historically marginalized by education systems. Even though distance learning isn’t the same as in-person experiences, we can still apply fundamentals of creating quality outdoor science teaching, research on how people learn, and effective pedagogy when we design distance learning experiences. BEETLES has five design principles that we use to guide us as we create any learning experiences:

- Engage directly with nature

- Experience instruction based on how people learn

- Think like a scientist

- Participate in equitable, inclusive, and culturally relevant learning environments

- Learn through discussions

(Read more about BEETLES Design Principles here).

BEETLES Design Principles are focused on making learning experiences learner-centered and nature-centered. It’s easy, especially in a video format, to fall back into primarily instructor-centered instruction, sharing facts about a subject instead of inviting learners to make observations and engage in critical thinking and discussion. When teachers are stressed, they often fall back on teaching in ways they’ve been taught as learners– and for many, that’s primarily in a lecture-based format. In a video or distance learning setting where it’s not possible to interact and see in-the-moment responses from learners, it’s also easy to revert to sharing information in a fun and entertaining way, but this lecture-based/instructor-centered approach doesn’t reflect what we know about effective learning and teaching. BEETLES Design Principles help our team put research on effective teaching into practice, to strive to be “guides on the side” instead of “sages on the stage” or “entertainers,” and to use student-centered and nature-centered approaches. And yes, distance learning can still be learner and nature-centered! In a distance-learning format, learners can still make observations of natural objects in their area, or through video footage, nature documentary footage, and photographs; can engage in science practices to learn; and can discuss and share ideas with others. We’ll delve into each of the design principles below and share some considerations for what this might look like in a distance learning format.

Engage Directly With Nature

Learners can still engage directly with nature in distance learning settings, but you might need to get creative about what that looks like. You can either bring the learner to nature or you might need to bring nature to the learner. You can bring the learner to nature by giving instructions on making observations of their surroundings, inviting learners to look at the window at the sky or passing birds or down at a tree, investigating houseplants or ants on the counter. You can also bring nature to learners by inviting them to engage with “on screen” nature, like an organism or a part of nature you show over video, nature video footage, live stream videos, or photography. Spending time in nature has clear benefits for health and wellness (Twohig-Bennett and Jones, 2018) Spending time with nature on a screen has benefits too (Jo, Song, Miyazaki, 2019).

General recommendations

- Offer instructions and guidance to engage learners in making observations, asking questions, and making connections, then model following the instructions before pausing to invite learners to begin. Modeling could include making observations or asking questions out loud to yourself, or with someone nearby, focused on objects viewers can see too (e.g. if you’re modeling making observations of veins in a leaf, make sure you have close-up footage of the leaf good enough so learners can see the veins you’re talking about).

- Give learners time and guidance to make observations, ask questions, and make connections to their prior knowledge and life experiences.

- Make use of journaling as a tool for learners to record their observations and ideas, encouraging them to use writing, drawing, and numbers.

Recommendations For Engaging Learners With “OFF-SCREEN” Nature

(learners observe nature from their surroundings)

- Consider access and equity when inviting learners to find parts of nature to study. Don’t structure a distance learning experience around things only some learners will have ready access to, and don’t assume every student will have a yard– but also don’t assume that if learners don’t have a yard they don’t have access to nature.

- Frame “nature” as something around us all the time. Offer many examples of what “nature” is, and offer many options and general categories of what learners can observe, like “a plant,” “something green,” “the sky,” etc. Include common household organisms and objects from nature, like ants, spiders, pets, fruits, vegetables, seeds, mushrooms, shells, feathers, rocks, sticks, and houseplants, or plants or animals learners can observe just outside a window, in a yard, along the sidewalk, or any other available tiny or large green spaces among options for what learners can observe. It could also include images or videos chosen by learners from books, internet, videos, and/or from still images shared on hard copy by the educational organization.

- Avoid creating a “nature hierarchy” where learners with yards or gardens are viewing “better” nature than those looking at houseplants or nature videos. Pay careful attention to the examples you give and the language you use to describe experiences. Using words like “just” or “only” as in, “If you just/only have access to nature videos, that’s ok, too” can unintentionally send the message that those nature experiences are less-than.

- Offer learners time to interact with and to apply science practices to the part of nature they are observing. When you ask learners to make observations of something in their surroundings, encourage learners to turn the video off and actually leave their devices, then come back when they are ready. Add a pause screen with text to remind learners of any instructions you’ve given (after giving the instructions verbally).

- When possible, give learners some autonomy in choosing objects that are interesting to them. Sometimes these might not be nature objects.

- Give appropriate safety tips regarding spiders, mold, poison oak or ivy, and any other local hazards.

Recommendations For ENGAGING LEARNERS WITH “ON-SCREEN” NATURE

(learners observe nature in video or still images on screen)

- If you are making a video or livestream featuring natural objects, include extended close up footage of the parts of nature that are the focus of study of a high-enough quality that learners can make good observations (e.g. If it’s a creek exploration, include lots of closeup footage of macroinvertebrates, if it’s about fungi, include lots of close-up footage of the fungi). You can also include still images, and give viewers time to make observations of these too.

- When sharing nature through video footage or still images, include times when the instructor is quiet so learners can make their own observations, hear nature sounds, think for themselves, and have their own experience and connection with the subject matter. Pause for longer than you think you might need to. Communicate how much time learners will have to focus on the natural object (e.g. “I’m going to be quiet for two minutes so you can make your own observations.”)

- Avoid making a video or conducting a class on some part of nature that you can’t get very good footage of (e.g. a quickly moving bird, etc.) If you’re offering a live, interactive experience, practice beforehand to make sure you’ll be able to get good footage.

- In a pre-recorded video, let learners know when to pause the video to observe or draw, or invite learners to choose a frame to freeze in the video, and take time to observe more closely.

- Keep the learner’s experience in mind! Regardless of the format you’re using, an interactive experience is more engaging and effective than an experience in which the learner is in a passive role, so figure out key opportunities for learners to observe, practice, discuss, and reflect. Avoid creating videos or classes that mostly feature the leader interacting with, talking about, or observing nature, while the viewer only watches the leader interact with or discuss nature.

Think Like a Scientist

In a distance learning experience, learners can engage in science practices as they engage directly with nature, on-screen or off-screen.

RECOMMENDATIONS:

- Invite learners to engage in science practices– making observations, asking questions, making explanations based on evidence, obtaining, evaluating, and communicating information, focused on on-screen or off-screen nature.

- Share curiosity tools, such as the prompts I notice, I wonder, It reminds me of, or I think maybe or questions such as: Can I identify any patterns? Is there evidence of a cause and effect relationship? What parts make up this object/phenomenon? Curiosity tools like these will support learners to be independent learners in all academic and disciplines, as well as with social-emotional learning.

- When you invite learners to use curiosity tools or engage in science practices, model using them yourself. Don’t just say “OK, say I notice!” Offer scaffolding, guidance, and examples, such as “Let’s focus on making observations. Observations are what we can find out using our senses of sight, hearing, smell, taste, or touch. An example of an observation is ‘I notice this leaf is a lighter green on the top than it is on the bottom.”

- After an experience, invite learners to reflect on how engaging in science practices has supported their learning. This builds learners’ competency, which is related to supporting intrinsic motivation, and increases their capacity as learners.

- Introduce science content or ideas after learners have had the opportunity to make explanations and try to figure things out. After introducing content, offer the opportunity for learners to apply that new knowledge.

- Avoid lecturing for the majority of the distance learning experience. Focus on offering just a few science ideas per session. Mix sharing content with discussion, and time for learners to write or share ideas with peers. Note: see more on facilitating discussion in distance learning below.

Learn Through Discussion

Discussion is critical for learning. We use the word “discussion” to refer to any exchange of ideas. In a distance learning setting (or any setting for that matter), discussion can be multimodal and can include speech, writing, engaging through chats, or using other online forums for sharing ideas. Learners can engage in discussion with those around them at home, or with others online.

RECOMMENDATIONS:

- Use thoughtful, interesting broad questions to invite student learning, thinking, and discussion (, and use the discussion map as a tool (check out a few more broad questions here: crosscutting concepts sheet).

- Invite learners to share ideas with family members or peers, especially if they have no way to share with others online, or to engage with each other by commenting on a live stream or pre-recorded video.

- In a live learning experience

- Engage learners in discussion in real-time. learners can share ideas through chatting, having discussions in breakout groups, recording ideas in a shared Google Doc, a Padlet, or some other online platform). On a platform like Seesaw, learners can choose whether to communicate ideas through drawing, text, or uploaded videos or photos.

- Be clear about exactly how learners can contribute ideas and avoid putting a value judgment on any particular kind of engagement, e.g. “you can share a comment out loud or type a comment into the chat and I will share it with the group.”

- Use wait time and facilitation moves to encourage equitable participation in discussion. Pause throughout a discussion to offer time for learners who haven’t participated as much to share (e.g. “I’m going to wait now and invite anyone who hasn’t spoken yet to share a comment.”)

Experience Instruction Based on How People Learn:

When planning out a distance learning experience, remember to use the learning cycle, just as you would any other kind of learning experience.

RECOMMENDATIONS:

- INVITATION: How are you going to engage the learners and pique their interest in the topic? How can you invite learners to access their prior knowledge about the topic? Examples: “Think, write, or discuss this question: What have you noticed or heard about leaves before? Or… What are some positive experiences you’ve had with rollie pollies? Etc.”. When posing an invitation question in distance learning, consider using a chat feature if you can to have all learners respond quickly, breaking learners out into small groups (e.g., using breakout rooms) to access prior knowledge together, or inviting learners to write, draw, or otherwise reflect individually on a question.

- EXPLORATION: Offer time for learners to observe, ask questions about, and make connections to the subject of the learning experience. Use broad questions to guide learners’ observations, to invite them to begin figuring out concepts, and to build curiosity and interest in the subject of the learning experience. When offering exploration time in a distance learning setting, focus their attention on some aspect of “on-screen” or “off-screen” nature, then include time for students to share about their observations in a discussion, chat, or virtual whiteboard.

- CONCEPT INVENTION: Use broad questions to invite learners to explain what they’ve observed. Support learners to come up with ideas and make sense of what they’ve been studying. Offer a few bits of strategic content or science ideas, then invite learners to use this new content to deepen their understandings. Avoid sharing everything you know about the subject or extraneous information. Share just enough to support learners to increase their understanding and to increase their curiosity. Encourage learners to be invested in investigating and learning more. If learners have internet access, encourage them to look up more information for themselves. When engaging students in concept invention invite them to make explanations or figure something out about what they observed during the exploration, and to share their thinking in writing, in a discussion, or on a virtual whiteboard or discussion forum.

- APPLICATION: Offer opportunities for learners to apply what they’ve learned in some way(s). This might be applying ideas learners have learned through study of one organism to another organism, or through a discussion. In engaging students in application, consider using guided independent study time: inviting students to use their new knowledge in a conversation with a peer online or a family member; to make explanations or ask questions about some aspect of their home environment, or to engage in further research on the internet.

- REFLECTION: Learning and memory of what is learned is increased when learners have opportunities to reflect back on the learning experience: what their initial ideas were, what their ideas are now, what information or evidence helped change their ideas, what they did, what they wondered, etc. Use broad questions to invite learners to reflect on the learning experience, through discussion, through a chat feature, and/or through journaling. It’s ok to create space in online experiences for learners to individually reflect. Invite learners to turn off their video and/or audio and then return to the group at a set time. Invite learners to continue their learning on their own, after the experience.

Participate in Equitable, Inclusive, Culturally Relevant Learning Experiences

Many attributes of equitable, inclusive, and culturally relevant learning are integrated into the other BEETLES design principles, but here are some additional considerations for explicitly designing learning experiences for equity, inclusion, and cultural relevance.

RECOMMENDATIONS:

- Consider access: How can you make sure all members of your audience will be able to attend, and that all resources will be able to be received by your audience? This is why partnering with schools, districts, or community groups that have established relationships with learners and families can be important. Keep asking the questions: Who is missing? What are the formats that will be most accessible for distance learning for your audience(es)?

- Center equity:

- Consider who has been left behind by educational systems historically and who is currently left behind. As you determine the audience for your programming, consider what it would look like to disproportionately direct your distance learning efforts and resources on those communities?

- Center the learning discussion on a common experience all learners have access to. This could be footage within a video you’ve made, or in a separate video of nature that all learners observe. That then becomes the focus of the learning conversation. You could also use a common set of skills or science practices for learners to engage in “off-screen” with a part of nature everyone has access to, or a part of nature of their choice. Centering learning around a phenomenon everyone is observing attends to historic and current marginalization by being a counter to science learning experiences where participation is contingent on prior exposure to science ideas, and students who have had previous exposure to science ideas tend to be at an advantage.

- Consider cultural relevance:

- Invite and make space for learners to make connections to their prior knowledge and lived experiences, and invite learners to share these perspectives and ideas during the learning experience. Create opportunities for all learners to share expertise and learn from one another, not just from the instructor.

- Ask for feedback. To the extent possible, be in touch with the learners and communities you are serving. Create opportunities from the beginning to co-construct learning experiences, content focus and ask questions like, What is working? What isn’t? Who isn’t participating yet? What do they need in order to be supported to participate?

- Support relatedness: To the extent possible, build opportunities for social connection and build on learners’ existing relationships. This is a critical part of supporting intrinsic motivation, participation, and culturally responsive teaching. Ask yourself: How can learners collaborate or be in conversation during the learning experience? How can learners be in conversation and collaboration with someone they know and trust? This could be classmates, their teacher, family members, etc.

- Use the other BEETLES design principles to support you to create student and nature-centered learning experiences. Student and nature-centered learning experiences are more likely to be equitable, accessible, and cultural relevant for learners!

Closing Thoughts

If there is a playbook for distance learning in a pandemic, we haven’t seen it yet. Most of us are juggling many, often competing priorities with fewer resources than we did before! Most of us are doing the best we can, amid incredibly challenging, unpredictable, and constantly evolving situations. The BEETLES team is right there with you! We offer these thoughts and guidelines to support the ongoing delivery of outdoor science and environmental education with the goal of ensuring every learner still has access to the benefits of spending time with nature (even if it is virtual); and with the belief that every community benefits from the presence of young people with the knowledge, skills, and connections to improve quality of life, health, and social wellbeing for everyone.

References

Jo, H., Song, C., Miyazaki, Y., (2019). Physiological benefits of viewing nature: A systematic review of indoor experiments. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16

Loeb, S. (2020). How Effective is Online Learning? What the Research Does and Doesn’t Tell Us. Education Week. 39 (28), 17.

Twohig-Bennett and Andy Jones, “The Health Benefits of the Great Outdoors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Greenspace Exposure and Health Outcomes,” Environmental Research 166 (October 2018): 628–37, doi:10.1016 /j.envres.2018.06.030.

6 Responses to “Designing Outdoor Science and Environmental Education Distance Learning Experiences”

Thanks for this. As you have said “Most of us are doing the best we can, amid incredibly challenging, unpredictable, and constantly evolving situations.”

Our program has put out lots of online content working in conjunction with our County Office Science Curriculum coordinator. Much of it is instructor centered and on topics requested by the county but we also try to engage the learner.

This page will be required reading for all our naturalists, that way we can continue creating engaging AND entertaining online content for our learners.

One note though, under your “RECOMMENDATIONS FOR ENGAGING LEARNERS WITH “ON-SCREEN” NATURE”

You mention “Communicate how much time learners will have to focus on the natural object (e.g. “I’m going to be quiet for two minutes so you can make your own observations.”)

In the online video world, 2 min of screen time of the same image with no commentary or action is an eternity that will be escaped by one click. IRL not so much so, but online it doesn’t work. Better is the recommendation you made to have instructions to pause it; or perhaps interject prompts and/or entertaining comments like (Hey Emma, look at screen not out the window, or whatever) to break up the monotony.

Just an observation I have made when watching young people online..

Thanks again,

DT

Hey Dean,

Thanks for sharing your thoughts!

This is outstanding. Thank you.

Lots of logical, useful information; thanks for summarizing key ideas on ways to transition from in-person interactions to distance learning experiences.

I think the Reflection part of the distance earning process is one of the most difficult to integrate into lessons because there’s a lot of ground to cover in 3-5 minute videos. The lesson would have to be highly refined and condensed. At our site we’re tasked with creating lessons for the Canvas platform for use by county educators. We have very specific NGSS protocols we’re supposed to address in order to support/supliment the district’s program.

Id love any suggestions.

Thank you for thinking through this and sharing this guide. Big equity issues: unreliable access to internet and appropriate devices forces us to rely on paper & physical objects, which can be distributed by mail or at food pick-up locations. Challenges: interaction with others, direction reading ability of students and adult caregivers.

Leave a Response