Partnerships in the Pandemic Spotlight: Portland Public Schools

By Cristina Edwards and Emilie Lygren

Brooke Teller is the STEM Coordinator/Science Coach for Portland Public Schools, a school district in Portland, Maine. After 21 years as a high school science teacher, Brooke shifted to a role as the district’s STEM Coordinator. During the pandemic, she has taken on the role of Interim Outdoor Learning Coordinator for the district’s 17 schools. Since being in this role, Brooke has coordinated the creation of 156 outdoor learning sites.

We spoke with Brooke about how she leveraged CARES funding and the support of local businesses to provide district-wide support for teachers to pivot to teaching outside as much as possible during the pandemic. There was a lot of community support for outdoor learning, both from school administrators and local businesses.

We spoke with Brooke about how she leveraged CARES funding and the support of local businesses to provide district-wide support for teachers to pivot to teaching outside as much as possible during the pandemic. There was a lot of community support for outdoor learning, both from school administrators and local businesses.

This interview is part of our Partnerships in the Pandemic series on outdoor, in-person learning.

BEETLES: Share a little bit about your role, and how this district-wide approach to outdoor learning during the pandemic came about.

Brooke: Last year was my first year as the STEM Coordinator for Portland Public Schools. I was working on developing an elementary science curriculum, and then Covid happened and everything changed. I shifted and became part of the district’s working group to figure out what the fall would look like.

It became clear that we wanted to do something around setting up outdoor sites so that teachers could get outside. We wanted them to be able to do what they do in the classroom, but do it outside. At that point, we weren’t necessarily thinking of nature-based education. We really just wanted to allow teachers to teach outdoors.

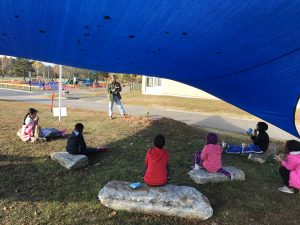

There was a group of parents and board members and other community partners that were really advocating for Portland Public Schools to do something beyond just two outdoor classrooms at each building. I began working with the community, parent groups, and the district to set up 156 outdoor learning sites at our 17 buildings. Most of them are fairly informal – buckets, stumps, easels.

The board and the school administration, made a strong suggestion at the beginning of the fall which stated that we hope students are outside at least 50% of their day. Schools and school administrators really did a good job of figuring that out. The morning message could be outside, snack time could be outside, lunch could be outside, even if the teachers couldn’t figure out how to do their curriculum outside. It’s about finding the balance between the teacher contracts, and what we can and can’t ask folks to do.

BEETLES: Share a little more about how you supported teachers within the district to teach outdoors. Did you collect materials? If so, how was this funded?

Brooke: The first piece was making sure teachers had what they needed to teach in the outdoor learning areas – easels, whiteboards, and seating for students. And then, the students needed to have materials as well. With the help of some of our AmeriCorps volunteers, we built out 5,000 student kits, which were drawstring backpacks with clipboards, notebooks, and writing utensils. This allowed kids to have their own items and not share those types of items as a Covid safety protocol.

Brooke: The first piece was making sure teachers had what they needed to teach in the outdoor learning areas – easels, whiteboards, and seating for students. And then, the students needed to have materials as well. With the help of some of our AmeriCorps volunteers, we built out 5,000 student kits, which were drawstring backpacks with clipboards, notebooks, and writing utensils. This allowed kids to have their own items and not share those types of items as a Covid safety protocol.

I knew that I had CARES funding to use from the district. It wasn’t unlimited, but I could ask for things and we could order those. We also have the Foundation for Portland Public Schools, and community members who wanted to support this initiative donated around $5,000.

We were also lucky that the advocacy group with the parents and the community members also included the Portland Society for Architecture. It was from that group that we were directed to Transformit, which is a company that makes architectural shades. With CARES funding, we purchased two shades per building, so now each site has at least two outdoor learning areas with some sort of covering.

As it started to get colder, we had to start getting hats, gloves and snow pants. A lot of our students aren’t able to access those types of things on their own. I think we have close to 800 hats and pairs of gloves. I ordered 600 snow pants. When those came in, I went to where they’re being stored, and it was just a wall of boxes. I was like, “Wow. That’s a lot of snow pants.” They have since been distributed.

We’re hoping that those will encourage kids to be outside. The students will get to take them home, because when they’re home on their remote days, we don’t want them stuck inside. We want to encourage them to go out and do some nature journaling or, just observe what’s going on. Go for a walk. We hope that having the right equipment and gear will help them to do that.

BEETLES: What have been some successes and challenges that have emerged?

Brooke: I put out a survey to find out how many teachers were accessing the outdoor sites. At that time, about 50% of respondents said that they were using outdoor sites at least once a week, if not twice a week. Initially, I was disappointed that 50% was the response. But 0% was the previous answer to that question, so I’ll take 50%. That means we’re moving in the right direction.

Some of the barriers that teachers mentioned to why they weren’t getting out were things like the noise, the weather, and professional development. Some of the challenge is just about comfort. A stump is just not as comfortable as other chairs. Some places don’t have WiFi outside. These architectural shade structures are supposed to last seven years. We lost two of them to vandalism already, and two more are quite damaged. They look like really cool trampolines, or climbing structures. I never even thought about the fact that kids were going to climb on them and jump on them during non-school hours. Those ones got turned into very expensive trampolines. We’re going to do some teaching about the structures in the spring, so that maybe that doesn’t happen again.

But we’ve also seen many successes. I’ve had teachers just talk about the little things students notice, like going out in the morning and noticing the buckets have condensation on them. They also talk about the weather every day.

Some teachers were concerned that maybe students would be more distracted outside because there’s so many things to look at, but they actually reported their students were less distracted and asked to go inside to use the restroom less than they did when they were in their regular classes.

Teachers also have lots of different creative ideas. A lot of our elementary school art teachers are trying to be outside as much as possible. I visited one school and they were doing some pressings of wildflowers. They had the flowers between two pages, and the students were hitting them with hammers to get the pigment out. That’s totally fun to bang things with hammers, and they might not do that in the classroom because it would be too disruptive or noisy. We do see that creative spirit in teachers come out when they’re given this new environment to be in.

We had Carpenters Local 349 build 204 easels so every school has 12 easels to put in their outdoor classrooms, and white boards to use on those easels. That’s just one example of a community group that heard we had a need, and jumped in and offered to volunteer help.

We had Carpenters Local 349 build 204 easels so every school has 12 easels to put in their outdoor classrooms, and white boards to use on those easels. That’s just one example of a community group that heard we had a need, and jumped in and offered to volunteer help.

We are in a fourth phase of the process where we are getting professional development for teachers on how to use the outdoors in their teaching. We have gotten some grant money so that Maine teachers can work with Maine Audubon to have them help deliver in-person outdoor sessions or virtual sessions. We also have upcoming professional learning sessions with Juniper Hill School. This is all helping build teacher capacity for being outside, and giving them ideas about what to do with the surroundings for each of their schools. That’s pretty exciting.

It’s really shifted from not just, “Let’s just be outside,” but now, “How can we use outside?”

BEETLES: How have you considered equity and access in this process, and where could you improve in this area?

Brooke: I was very vocal with our parents and community advocacy group about equity issues. Our elementary schools are in different parts of the city, and the demographics of those schools differ greatly. One school has 80% free and reduced lunch, and then another one has a limited number of students with free and reduced lunch. This also means the ability of their PTO or PTA to acquire funding and items for their schools is variable. One of our elementary schools was able to buy their teachers collapsible wagons and camp chairs and all the bells and whistles to make outdoor learning happen more easily. This was amazing and awesome, but I couldn’t do that for all of the teachers across the whole district. It became a conversation about what is equitable to make sure that all of our schools have what they need. Sometimes that means we can’t all have the bells and whistles, because I need to make sure that everyone has access to the most essential components.

We have a large community of English language learners and a refugee population in Portland. We are working on parent communication to explain why we are going outside for learning. We made sure that we were being really sensitive and thoughtful about intentional communication to explain why we were doing this differently.

I’m looking at how our schools can have experiences that are shared across schools, regardless of what their PTO can afford. For example, we would love to make sure that all fourth graders are able to go to the same field trip and have a shared experience. My hope for those trips is that they are all outdoor, nature-based places that we’re going to get to take our students to.Our district needs to ensure that our students have a shared and equitable experience regardless of the school that they’re in.

BEETLES: What are your plans for outdoor learning in your district in the future, both in the short term and in the longer term? Would you consider continuing to offer support and infrastructure when pandemic “ends” or when schools return permanently to in-person instruction within your district?

Brooke: As a district, I know the commitment is to continue outdoor learning beyond this. I’m advocating that they hire someone to oversee this full time. I’m the STEM Coordinator, and there are clear intersections between outdoor learning and science. It would be my hope that I can continue to offer the professional development that teachers need to build capacity to have their students outside. We need to look at building permanent outdoor infrastructure.

Brooke: As a district, I know the commitment is to continue outdoor learning beyond this. I’m advocating that they hire someone to oversee this full time. I’m the STEM Coordinator, and there are clear intersections between outdoor learning and science. It would be my hope that I can continue to offer the professional development that teachers need to build capacity to have their students outside. We need to look at building permanent outdoor infrastructure.

Those are the next big steps: the district-level move, and then supporting curriculum and professional development for teachers in the spring and beyond.

BEETLES: Do you have any recommendations or thoughts for outdoor education organizations seeking to form partnerships with K-12 schools or districts during the pandemic?

Brooke: This work doesn’t happen without the parent community advocacy group. For us, this group had always been engaged, even before the pandemic. We have garden outdoor classrooms at many of our elementary schools. We’ve had other successes along the way. Even if a school just sets up one or two outdoor sites and pilots them, things start to build from there and schools see how it could work.

The parent and community group was really important to convincing the district that it should be done, and be that it could be done. For example, winning the support of the superintendent to shift my whole role from what I had been originally hired to do into something else. The buy-in piece is really big. From there, it’s a lot of cheerleading. I’m telling teachers, they can do it, and giving them ideas of how they can do it.

There are huge intersections in the outdoors for lots of learning beyond science. For nature journaling, for example. I’m using the Science NGSS standards, but looking at the speaking and listening standards. I’m showing teachers that if they go outside and do some nature journaling, students could be writing and tackling one of the literacy standards at the same time. I think teachers need to see that working outside is not more work. It’s just doing what they need to do already, but differently.

I’m working with our social studies lead teacher who is working on Native Wabanaki studies as related to social studies. For third grade, we’re going to be looking at a local river that the Wabanaki People would come to seasonally to catch salmon. As colonizers came in, it became a heavily dammed river, and the salmon couldn’t run anymore. This river is walkable for some of our schools. It’s a very place-based opportunity to show the kids what it means to be a water protector and how important this place has been to the Wabanaki People for thousands of years.

It’s that type of cheerleading; being able to say, “You can do this! You might not know all the science yet, but I will help you get there.” Our teachers know how to teach elementary students, they know how to teach literacy. Let’s just do it with science content instead of something arbitrary. Sometimes students have to write something about an informational text, why not have it be about salmon life cycles?

By the Numbers

- Students served: 5,750 of the district’s 6,750 students have participated in outdoor learning (the other 1,000 opted to be fully remote).

- Incidence of Covid at the time of this interview: 36 positive cases across 12 of 17 schools. Virtually no spread within buildings.

Read about how other programs are navigating outdoor, in-person learning: Partnerships in the Pandemic.

Leave a Response